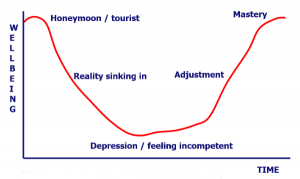

You are unlikely to experience that if you go to another country for a short vacation. Two weeks of sunbathing on the Spanish costa’s, or of walking the Welsh Coastal Path, does not count here, as you will probably never get out of ‘the tourist bubble’. But if people move from one culture into a different one, for a longer period of time, many report something like this cultural adaptation process. That process is sometimes also referred to as ‘culture shock’, but in this post I prefer the term ‘cultural adaptation´.

During the ‘honeymoon phase’ (or ‘tourist phase’) the mood is high. You experience a sense of curiosity and optimism, and you focus on the positive aspects of the new environment. The welcome, the feeling of being wanted and expected (in case of a voluntary migration), there is the desire to meet new people.

Usually this up-beat mood doesn’t last. Reality starts to sink in. You start to miss your family and friends more and more. Getting meaningfully connected with people in the new host culture often proves more difficult than expected, as the ‘rules of the local social game’ are often hidden below the surface, and difficult to grasp. The local do’s and don’ts are not always easy to incorporate (if you recognize them for what they are at all). You may miss the food, the habits and rituals from home, and so on.

During the third phase you can feel really low, at times. The homesickness is at its biggest. You may feel incompetent (‘I must be doing something wrong because I haven’t adapted to the new culture yet’, forgetting that this adaptation is not just a switch you can flip).

If these feelings hit inwards, they can translate into feeling depressed. If they hit outward they may translate as hostility towards the new host culture. And this inward and outward translation may actually alternate on a daily basis.

During this phase you can often see that people have a tendency to work ever longer hours. This is a strategy to not feel the pain and discomfort. In the short term this helps, but in the long run it only increases the risk of a burn-out. Engaging in non-work related activities is probably a more fruitful strategy.

Slowly but certainly most people start to adapt: the adjustment phase. Either you manage to incorporate some habits of the new host culture in your own behavioral repertoire, or at least you find coping strategies (‘It will never be my thing, but I can deal with it’).

Some people, if they are adaptive enough,and have a bit of a cooperative environment, can (almost) completely master the new culture in the end. In time they may find themselves to be a good cultural mentor for other newly arrived migrants.

Why am I telling you this? Well, I am not telling you this to scare the living daylights out of you (I say to newly arrived in particular). I am telling you this to make the point that, if you experience something of the sorts (or did experience it in the past), it is not your fault! It is a normal reaction to the abnormal circumstance of the migration.

My recommendation would be to not shy away from these feelings, but rather to make them explicit, to talk about them. Find like-minded people, share the experience, maybe give one another tips and suggestions. You may blame the locals, if it makes you feel better, but let me emphasize: it is not their fault either. They just are who they are too.

As a final addition to the above: an interesting phenomenon is often observed when the migrant in question returns home after a longer period abroad. The same thing as described above may occur there! It is called ‘re-entry shock’ or ‘reverse culture shock’. And it is a nasty one, because most returnees don’t see it coming.

Going abroad you usually ‘brace for impact’, although you may not know what this impact will be like. But going back home you expect to ‘finally have things normal again’. Often they will not. Not because ‘home’ has changed so much, but because you have.

Let me give an example for someone who has been in the Netherlands for a longer period of time, but the same mechanism goes for other countries. Believe it or not, but after being in the Netherlands for a considerable period, you will have ‘Dutchified’, to a certain extent 😉 🇳🇱.

You have more or less adapted to the Dutch environment, sometimes to the extent that you now may feel a stranger at home. And you may say or do things that are in accordance with the norms of (in this example) the Netherlands, but that may raise eyebrows at home: ‘Excuse me, what did you just say´?

And also: you have a zillion stories to tell. But the people at home haven’t ‘been there and done that’. In other words: they do not have the mental frame of reference to understand the relevance of the stories that you so much want to share.

So far for the blog post of this month. For those whom it concerns: I wish you happy adaptation!